Chitty Chitty Bang Bang the Magical Car has had a lick of paint and is all set to go-go-go!

Here you can find out more about the history of Chitty, her creator Ian Fleming and, more importantly, start reading Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Flies Again now with an exclusive peek at the first chapter!

Here you can find out more about the history of Chitty, her creator Ian Fleming and, more importantly, start reading Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Flies Again now with an exclusive peek at the first chapter!

A Note from Frank

The very first film I saw in the cinema was Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. I remember two things about the occasion – one was that we were taken to the pick'n'mix in Woolies and actually allowed to choose our own sweets (I went for Cherry Lips). The other was the moment when Chitty drove off the edge of the cliff and the whole building rang with howls, first of fear and then frustration, as the image froze and the word 'Intermission' blazed across the screen. I sat through the next ten minutes not even looking at the sweets I'd so carefully picked and mixed, just waiting for the film to start up again.

It was the day I discovered that a story could be even better than Cherry Lips!

Even now, whenever I come across a really heart-stopping moment in a script or a story I always think of it as a 'Chitty falls off the cliff' moment.

Because I didn't want the film to be over, I followed the car's smoky trail to the library and found Ian Fleming's book Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car, which he'd written for his son, Caspar, in 1964. I thought that if I read it I would see the whole film again inside my head. I was taken aback to discover that the book was very, very different from the film. The mum isn't dead. There's a different villain. There's a recipe for fudge! I suppose this must have been the moment I learned that films and books – even when they're telling the same story – each have a different kind of enchantment. And that there might be more than one – or more than a hundred – ways to tell the same story. As the old Tuscan proverb says, 'The tale is not beautiful if nothing is added.' Which obviously brings us to the idea of a sequel.

I have no idea what made the Flemings think of asking me to write the sequel. I haven't asked them in case it's all a case of mistaken identity. I wasn't sure whether to say yes at first, but when I mentioned it at supper in my house, any doubts I might have had about whether the book actually needed a sequel were shouted down. Everyone wanted me to do this. So I went back to the book for the first time since I was a boy and was delighted to discover that, first of all, it's really good and, secondly, it's crying out for a sequel. The original book ends with the car heading off into the sunset with the family on board. They were surely going to have more adventures. But Fleming sadly died before he could say what those adventures might be.

It's also one of the very few stories in which the whole family goes off on the adventure – usually children have to be sent away to school or evacuated or bereaved or fall through a time vortex before an adventure can start. I liked the challenge of creating a children's story with proper adult characters and relationships in it.

Finally I was absolutely thrilled to discover that Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was a real car, built by Count Zborowski in an attempt to break the world land-speed record in 1921. I've had a lot of fun – and am planning to have a lot more – just kicking this story up and down the pitch, with history at one end and fantasy at the other, mixing up the real history of aristocratic motor racing with the details of motor mechanics and the silly magic of a flying car. Somewhere in amongst all the fun, though, I found it strangely emotional to go and revisit that boy with the bag of Cherry Lips and ask if he could help me restore an old-fashioned contraption and make it fly again.

It was the day I discovered that a story could be even better than Cherry Lips!

Even now, whenever I come across a really heart-stopping moment in a script or a story I always think of it as a 'Chitty falls off the cliff' moment.

Because I didn't want the film to be over, I followed the car's smoky trail to the library and found Ian Fleming's book Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car, which he'd written for his son, Caspar, in 1964. I thought that if I read it I would see the whole film again inside my head. I was taken aback to discover that the book was very, very different from the film. The mum isn't dead. There's a different villain. There's a recipe for fudge! I suppose this must have been the moment I learned that films and books – even when they're telling the same story – each have a different kind of enchantment. And that there might be more than one – or more than a hundred – ways to tell the same story. As the old Tuscan proverb says, 'The tale is not beautiful if nothing is added.' Which obviously brings us to the idea of a sequel.

I have no idea what made the Flemings think of asking me to write the sequel. I haven't asked them in case it's all a case of mistaken identity. I wasn't sure whether to say yes at first, but when I mentioned it at supper in my house, any doubts I might have had about whether the book actually needed a sequel were shouted down. Everyone wanted me to do this. So I went back to the book for the first time since I was a boy and was delighted to discover that, first of all, it's really good and, secondly, it's crying out for a sequel. The original book ends with the car heading off into the sunset with the family on board. They were surely going to have more adventures. But Fleming sadly died before he could say what those adventures might be.

It's also one of the very few stories in which the whole family goes off on the adventure – usually children have to be sent away to school or evacuated or bereaved or fall through a time vortex before an adventure can start. I liked the challenge of creating a children's story with proper adult characters and relationships in it.

Finally I was absolutely thrilled to discover that Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was a real car, built by Count Zborowski in an attempt to break the world land-speed record in 1921. I've had a lot of fun – and am planning to have a lot more – just kicking this story up and down the pitch, with history at one end and fantasy at the other, mixing up the real history of aristocratic motor racing with the details of motor mechanics and the silly magic of a flying car. Somewhere in amongst all the fun, though, I found it strangely emotional to go and revisit that boy with the bag of Cherry Lips and ask if he could help me restore an old-fashioned contraption and make it fly again.

History

Ian Fleming and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car

Ian Fleming is best known for creating the very, very famous spy James Bond, secret agent 007. He wrote fourteen books about James Bond with the well-known titles such as Casino Royale, From Russia with Love, Dr. No and Goldfinger.

Ian Fleming had a passion for cars, and in the James Bond books he wrote wonderful descriptions of cars such as a Bentley Continental and an Aston Martin. When he was still a boy at school he had been to visit a house in Kent where there was a very fast and very noisy racing car. It belonged to an eccentric racing driver called Count Louis Zborowski. The car was known as Chitty Bang Bang.

It must have created a deep impression on the young Ian Fleming because when, forty years later, he decided that he would write a story for his small son Caspar about a car that could fly, he described a magnificent green car with 'rows and rows of gleaming knobs on the dashboard', 'a cream-coloured collapsible roof' and huge exhaust pipes of 'glistening silver'. He named it Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Ian Fleming was born in 1908 and died in 1964. He wrote Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car in 1962. It was published as three books in 1964. Sadly Ian Fleming never saw the finished books as he died of a heart attack a couple of months before publication.

The film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, made in 1968, was based on Ian Fleming's book. Roald Dahl wrote the screenplay and brought new elements – the Child Catcher for instance – to the story.

FIND OUT MORE AT WWW.IANFLEMING.COM

Ian Fleming is best known for creating the very, very famous spy James Bond, secret agent 007. He wrote fourteen books about James Bond with the well-known titles such as Casino Royale, From Russia with Love, Dr. No and Goldfinger.

Ian Fleming had a passion for cars, and in the James Bond books he wrote wonderful descriptions of cars such as a Bentley Continental and an Aston Martin. When he was still a boy at school he had been to visit a house in Kent where there was a very fast and very noisy racing car. It belonged to an eccentric racing driver called Count Louis Zborowski. The car was known as Chitty Bang Bang.

It must have created a deep impression on the young Ian Fleming because when, forty years later, he decided that he would write a story for his small son Caspar about a car that could fly, he described a magnificent green car with 'rows and rows of gleaming knobs on the dashboard', 'a cream-coloured collapsible roof' and huge exhaust pipes of 'glistening silver'. He named it Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Ian Fleming was born in 1908 and died in 1964. He wrote Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car in 1962. It was published as three books in 1964. Sadly Ian Fleming never saw the finished books as he died of a heart attack a couple of months before publication.

The film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, made in 1968, was based on Ian Fleming's book. Roald Dahl wrote the screenplay and brought new elements – the Child Catcher for instance – to the story.

FIND OUT MORE AT WWW.IANFLEMING.COM

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Flies Again

Chapter One

Chapter One

Most cars are just cars. Four wheels. An engine. Some

seats. They take you to work. Or to school. They bring

you home again. But some cars – just a few – are more

than cars.

Some cars are different.

Some cars are amazing.

And the Tooting family's car was absolutely definitely not one of those.

Not amazing.

Not different.

It was so undifferent and so unamazing, in fact, that on the last day of the summer term when Lucy and Jem strolled out of the school gates and into the holidays, they walked straight past it. They didn't even notice it was there until their father popped his head out of the window and shouted, 'Lucy! Jem! Jump in! I'm giving you a lift!'

'I don't need a lift,' said Lucy, who was fifteen years old. 'I need to be alone.' Lucy always dressed completely in black, ever since last Christmas.

'Why aren't you at work?' asked Jem.

'Special occasion,' said Dad. 'I have Big News.'

'Good Big News? Or Bad Big News?' said Jem, who was a bit of a worrier.

'All Big News is tragic,' said Lucy sadly. 'Nothing good is ever news.'

'Wait and see,' said Dad. 'First we'll collect Little Harry from the childminder.'

Little Harry hated being strapped into his car seat. As he struggled to get free, Jem said, 'You have to be clipped in, in case we crash.'

'I lost my dinosaur,' said Little Harry.

'Are you going to tell us the Big Bad News now?' asked Lucy.

'It's not bad news. First we'll collect Mum from the shop.'

'You don't usually collect me from the shop,' said Mum, as she climbed into the front seat. 'Has something terrible happened?'

'Tragic news,' said Lucy.

'What tragic news?'

'Not tragic news,' said Dad. 'Big News. Excellent Big News.'

'Well, what is it?'

'I lost my dinosaur,' said Little Harry.

'Oh no,' said Mum. 'Not the lovely red remote-control one that Santa brought you?'

'Can we stop talking about the dinosaur and talk about my news, please?' said Dad.

'What news?'

'Well . . .' said Dad, '. . . I think we're going to need a takeaway to help us celebrate.'

They got the Celebration Banquet for Four with an extra portion of Chicken in Black Bean Sauce for Lucy – who liked to eat black food whenever she could. When it was all set out on the table, the lovely spicy smells curling into the air around them, Dad finally told them the excellent Big News.

'Children,' he said, 'and wife – my Excellent Big News is that –' he looked around the table, enjoying their expectant faces – 'I never have to work again! What do you think of that!?'

'Wow!' said Little Harry.

'Brilliant!' said Jem.

'That was unexpected,' said Lucy.

'How come?' said Mum.

'Because,' said Dad, 'I have been sacked! Hooray!'

'Hooray!' yelled Little Harry.

'Hooray!' re-yelled Dad.'I'm pleased that you're pleased,' said Mum, 'but are you sure it's entirely excellent news?'

'If you have no job,' said Jem, 'doesn't that mean we'll be really poor and starve to death?'

'No,' said Dad. 'It means we'll be able to do whatever we want and go wherever we like. The word today,' he said, 'is opportunity.'

'I want my dinosaur back!' yelled Little Harry.

Dad explained the details. 'Since the day I left school,' he said, 'I have worked in a factory making tiny, tiny parts for really big machines. But now the company has a new contract making even tinier parts for even bigger machines. My fingers are just too big for the job. So they said they had to let me go.'

'Go where?' said Jem.

'Go anywhere we like,' said Dad.

'When you say anywhere,' said Jem, 'does that include abroad?' No one in the Tooting family had ever been abroad before.

'Anywhere,' said Dad, 'means anywhere in the world.' He smiled at Mum. 'And, dearest, you get first pick.'

Mum blushed a little and said, 'Well you always promised to take me to Paris.'

'Paris,' he said, 'is yours. The moment we are packed. Lucy?'

'Me?' said Lucy. 'I don't want to go anywhere. I want to spend my days in my room, now that I've finally got it the way I like it.' Lucy had got rid of all the ornaments and dancing certificates from her room, painted the walls and her bookcase black. Dyed her duvet. And her pillowslip.

'You must want to go somewhere?'

'I suppose I wouldn't mind seeing the pyramids. I could sit in the desert looking at the Sphinx and think about dead pharaohs, with their gold and jewels, lying there in the desert night. Dead, dead, dead.'

'I can see we're going to need to plan our route,' said Dad. 'Go and get that map of the world from your bedroom wall.'

'The map of the world isn't on my bedroom wall any more,' said Lucy. 'The colours were too bright – yellow and blue and pink. Pastel colours depress me.'

'But I've had that map since I was a little boy. I won it for being punctual. It says so on the back. What have you done with it?'

'I stuck it up on Jem's wall.'

'Jem—'

'It was completely out of date. There were countries on there that were shut down years ago and new countries that weren't even mentioned. Instead of France it had something called Gaul.'

'It was supposed to be a historical map.'

'That's what I said, out of date. I put it in recycling.'

'What? Do you know how often I had to be punctual to win that prize?'

'Why would you want an out-of-date map when there's really good satnav in the car? A map like that could be dangerous.'

'Dangerous? How?'

'If you tried to use it you would get lost. People get lost all the time. Cities get lost, even.'

'What cities get lost?' said Lucy.

'El Dorado. Camelot. Troy. Xanadu. Atlantis. They were all big cities once and now no one knows where they are. They got lost. I bet it was because of out-of-date maps.'

'Maps go out of date,' said Dad, 'because countries change. And people can go out of date because their fingers are too big for the machines. That doesn't mean they should be put in a bin. Just because something's out of date doesn't mean it's no use.'

'Dad, I was talking about maps, not fingers,' said Jem.

'I didn't mean—'

'And it's all fine anyway,' said Mum, 'because I took the map out of recycling again. Here it is . . .' She spread it out on the table and touched the back of Dad's hand.

'I've always been very proud of your father's punctuality,' she said. 'It's one of his most attractive qualities, along with his boyish smile.' Dad smiled his boyish smile.

'Now, Jem, you said you wanted to go to El Dorado. Show your dad where it is on the map.'

'I don't know where it is on the map. That's the point. It's lost. I was making a point about how easy it is to get lost. If a big city can get lost, a small person can get lost.'

'It's somewhere around here,' said Dad, pointing to South America.

'Well then,' said Mum, 'we'll stop and ask when we get to the general area. The locals are bound to know. Little Harry, what about you?'

'Dinosaurs!' yelled Little Harry.

'We'll try our best,' said Dad. 'So . . . what have we got? Paris for Mum, Cairo for Lucy, El Dorado for Jem—'

'I really don't want to go to El Dorado,' said Jem.

'. . . and last of all, the North Pole for me.'

'That's the South Pole,' said Jem. 'You've got the map upside down. See what I mean about how easy it is to get lost?'

'Can you really drive to the North Pole in a car?' said Lucy. 'Wouldn't you be overwhelmed by blizzards and buried in avalanches and left untouched and frozen in the snow for hundreds of years, like fish fingers? Dead, dead, dead.'

'No,' said Jem. 'Because our car's got four-wheel drive and a super de-icer. And satnav. It can go anywhere in the whole world and never get stuck and never get lost.'

That's when the doorbell rang.

At the door was a nice young man in a blazer with a plastic identity card clipped to his lapel. 'Hello,' said Dad, reading the badge, 'Bernard.'

'Good evening, Mr Tooting.' Bernard smiled. 'I work for Very Small Parts For Very Big Machines.'

'Oh!' said Dad. 'So do I!'

'Not any more you don't.' Bernard smiled again.

'Oh yes, I forgot.'

'Perhaps you also forgot that this car – with its satnav, four-wheel drive and super de-icer – belongs to the company?'

'Oh,' said Dad. 'I did forget that. Yes.'

'Keys, please.' Still smiling, Bernard put his hand out and Dad gave him the car keys. Bernard drove away in the car. Mum put her hand gently on Dad's shoulder.

'Never mind,' she said.

'I've got no job.'

'We'll manage,' said Mum.

'I've got big fingers.'

'I like your fingers.'

'I've got no car,' said Dad.

'We'll walk,' said Mum.

'Not to Paris.'

'No.'

'Not to Cairo.'

'No.'

'Not to El Dorado, or the North Pole. We'll never go to any of those places. We'll never go anywhere.'

He stood and watched until the car had disappeared around the corner.

'The word today,' he said, 'is stuck.'

Mum went back to the supper table.

'When your father comes back,' she said, 'he may well be very unhappy.'

'Why?' said Jem.

'Because he's got no job, no car and no prospects,' said Lucy.

'I wouldn't say no prospects,' said Mum.

'He's much too old to get another job.'

'I lost my dinosaur,' said Little Harry.

But when Dad came back to the table, he said, 'Pass me a prawn cracker, Jem,' and leaned back in his chair with a big smile on his face. 'I am so glad,' he said, 'that that car has finally gone. I never wanted to travel the world. Now I'll be able to concentrate on my plans for this house.'

'You've got plans for the house?' asked Mum. 'What sort of plans?'

'The word today,' said Dad, 'is home improvement.'

There was a terrible, blood-curdling scream, a scream that rattled windows seven streets away.

When Lucy woke up on that first day of the summer holidays, she was confronted with her worst nightmare. While she was sleeping, someone had somehow covered her black walls with jolly blue wallpaper with daisies on it.

'My eyes!' shrieked Lucy. 'The wallpaper is blinding me!' She covered her face with her hands and, peeping out through her fingers, saw Dad up a ladder hanging a strip of the blue daisy wallpaper.

'What do you think?' he asked. 'Thought I'd brighten the place up a bit. Your room was so gloomy.'

'I like gloomy,' said Lucy. 'Gloomy is the point. I worked hard on gloomy. I painted it with three coats of gloomy paint. And what is that terrible smell?'

A little cloud of thick black smoke was curling from a hot, bubbling hole in the top of her skull-shaped reading lamp. 'My skull,' she shrieked. 'My skull is melting!' The lamp was charred and twisted and slumped to one side.

'The light seemed a bit dim so I put a more powerful bulb in it. Maybe a bit too powerful.'

'I'm being poisoned by my own bedside lamp!'

From the next room came a cry of, 'Help! Help! Help me!'

'Oh,' said Dad. 'Sounds like Jem's awake.'

'It sounds like Jem's in mortal danger.'

'I think he's just really surprised at what I've done to his room.'

Jem had been woken up by a strange, electric whining. When he opened his eyes, a small blue object whizzed right past his face. He barely had a chance to blink when a small red object rattled past even closer. He just had time to see that the objects were car-shaped. Tiny cars were flying round his room, skimming by his face, like angry insects.

'Help!' he yelled, sliding under the duvet. 'Help!' He didn't shout anything more specific because he couldn't figure out what kind of help a person should ask for if attacked by tiny cars – presumably driven by tiny men.

The explanation was simple enough. When Dad was ten years old, he had woken up on his birthday to find that his dad had assembled an amazing Scalextric track in the bedroom he shared with his brother. It was one of the happiest memories of his life – a plastic racetrack, two racing cars – one blue and one red – and a little man with a chequered flag, all set up and ready to go. They spent the whole day racing each other round and round that track. For years afterwards they used pocket money to get extra track and the round circuit grew into a spaghetti of twists, turns, chicanes and flyovers. They grew out of it but Dad could never bear to give it away or throw it out so it had ended up in the loft. He always meant to get it down and fix it up so that Jem could play with it. Now that he'd been sacked he finally had the time to get the pieces down, make sure the wheels were oiled and the wires were snug, sneak into Jem's room and snap together a race course that whirled around the table legs, soared over his bed, swung in and out of the windowsill and filled the room with speed and the smell of hot metal.

'What do you think?' said Dad, sticking his head round the door.

'What's it for?'

'We can race against each other.'

'Haven't you heard of computers? We can race against each other on a range of platforms in any format we like. We can race as elephants, rockets, chariots – not red and blue plastic cars. And you don't have to tidy up afterwards and it's not dangerous. That's why people like to play on their computers and why they put this stuff in the dump.'

'How is this dangerous?'

'Electric wires, bits of plastic flying around the room at speed. Of course it's dangerous . . .' Just as he said that, the blue car missed the turn, shot off the end of the track, tumbled through the air and whacked Dad in the middle of his forehead. For a second it looked like he was going to fall over. Then, 'That's all part of the fun of it!' He smiled and wiped the blood away. 'The word today is fun.'

Little Harry had a dream about dinosaurs. It wasn't a nightmare. He loved dinosaurs and in the dream they were picking him up and throwing him to each other, slapping him into the air with their tails and bouncing him off their horns, and all the time he was laughing and gurgling. When he woke up, Dad was sitting on the end of his bed.

'I know what you're going to say, Little Harry,' he said. 'You say the same thing every morning. Every morning you say, "Play with me". Every morning I say I can't because I'm going to work. But this morning is different. Go on, say, "Play with me".'

'Dinosaur!' said Little Harry.

'No, like this . . . Play with me.'

'Please dinosaur.'

'Play. With. Me . . .' The moment Dad said this, there was a strange whirring from the toy box at the end of Little Harry's bed. The whirring was followed by a clicking.

'You're always asking people to play with you,' Dad explained, 'when they're too busy. So I've used some of the skills and expertise I learned in the twenty years I worked without complaint and never once being late at Very Small Parts For Very Big Machines. I have used those skills so that instead of playing with toys like other children, you will have toys that play with you!'

Little Harry was staring at the toy box. His eyes were growing wider and wider.

'Voice-activated,' said Dad. 'From now on, whenever you say "Play with me", your toys will just get up and play with you . . .'

Harry's eyes were now so round they looked as though they were going to fall out of his face. A dozen Playmobil men clambered out of the box and marched towards his bed, their plastic arms held out in front of them like tiny primary-colour zombies. They were followed by some wooden knights brandishing sharp little wooden lances, and a family of grinning yellow ducks that rocked themselves bit by bit across the carpet. Toy cars whizzed towards him from every dusty corner of the room.

Little Harry saw this brightly coloured army of toys coming towards him and he cried like a baby. He was a baby.

A large snake made of red and blue felt reared up from behind the washing basket and flung itself on to the bed. A massive fuzzy blue giraffe stood up, steadied itself and began to goose-step jerkily towards him.

'They all want to play,' said Dad. 'You want to play and they want to play. It's the ideal arrangement.'

The pterodactyl mobile that hung from Little Harry's lampshade spun faster and faster until the tiny pterodactyls broke free and came buzzing round his head like Jurassic fighter planes. Desperately Little Harry tried to bat them away.

'Don't worry, they won't hurt you.' Dad smiled. 'I fitted little sensors to the front so that they don't bump into you. I'm particularly proud of those. Well, you have fun. I'm going to go and make some tea.'

Dad strolled out of the room, but when Little Harry tried to follow him the big blue-and-red snake wrapped its fluffy coils around his middle and began to squeeze. Little Harry screamed louder than ever, though his screams were muffled slightly by the massive giraffe which was now headbutting him, softly and repeatedly. He was still there being cuddled by the snake and headbutted by the giraffe when Lucy came into his room to look for a paintbrush.

'Jem! Quick!' she yelled. 'Little Harry's toys have gone nutzoid!'

They peeled the snake off Little Harry and forced the giraffe back into the corner. They locked the little wooden knights away and tied the pterodactyls down.

'What happened?' said Jem once Little Harry had been rescued from his toys.

'Isn't it obvious?' said Lucy.

'Home Improvements,' said Jem.

'Dad has got to be stopped,' said both of them.

Truly Jem and Lucy thought that as soon as Mum found out about the headbutting giraffes and melting skulls she would put an end to home improvements. But that afternoon, as she trudged up the garden path after a hard day's work at Unbeatable Motoring Bargains, a very refreshing thing happened. The front door opened all by itself and a bright little voice said, 'Do come in. The kettle is on.'

'What a lovely homecoming,' said Mum, strolling into the kitchen just as the kettle came to the boil.

'I installed an automatic self-opening on the front door,' explained Dad, 'and hooked it up to the kettle.'

'My genius.' Mum smiled.

'The word today,' said Dad, 'is welcome home.'

'That's two words,' said Lucy.

'Dad made a robot snake that tried to strangle Little Harry,' said Jem.

'It was a cuddly snake. It was just cuddling him,' explained Dad. 'From now on, whenever you come home, the kettle will always be boiling.'

'Also, Jem's bedroom is now a death trap,' said Lucy.

'A work in progress,' said Mum, sipping her tea. 'Be patient. Your father can't improve every aspect of our lives in one day.'

'He made my skull melt,' said Lucy.

'Teething problems,' said Mum. 'Any man who can get a door to make a lovely cup of tea like this can do anything. Give him time.'

As far as Mum was concerned, a self-opening front door that made tea was a magnificent home improvement. The only problem was, it was magnificent for anyone who happened to be passing. When Mum came down next morning, the milkman and the paper boy were already in the kitchen guzzling tea and Krispies. The paper boy looked hard at Mum and said, 'I know you from somewhere.'

'I live here,' said Mum. 'Those are my Krispies.'

'Thanks for sharing,' said the paper boy.

There was a sudden draught of cold air as the front door opened itself and invited a passing jogger in.

'I,' said Mum, 'have to go to work.'

Off she went.

The postman, the milkman and the paper boy all left to resume their work quite soon after Mum, but the jogger was not in any hurry. He was still there when Lucy and Jem came down to breakfast. Still there when Dad came in to cook lunch. Every now and then he did stand up as if about to leave, but each time he did the front door would ask another jogger in and the joggers always seemed to know each other and have plenty to talk about. Slowly the kitchen filled up so that by four o'clock it was an impenetrable mass of joggers. If Jem or Lucy looked in, someone would push a mug at them and say, 'More tea, please,' or, 'We've run out of milk.' The children parked themselves miserably on the bottom stair, waiting for the day to end.

'I'm hungry,' said Little Harry.

'We have been excluded from our own kitchen,' said Lucy.

'I'm hungry,' said Little Harry.

'So am I, but there's nothing we can do about it just now.'

'I'm hungry,' said Little Harry.

'Yes. You've mentioned this. Why can't we just be an ordinary family like we used to be?'

'You were ordinary,' said Lucy. 'I never was.'

Outside the house someone was happily honking a car horn.

'Who's that?'

'It doesn't matter who it is,' said Lucy. 'It doesn't matter if it's Lord Voldemort and his wicked stepmother, the front door will still open and ask them in for tea.'

The front door did open and did ask them in for tea, and when it did they saw, standing in the road, a dirty blue-and-cream camper van with rusty bumpers and one window missing.

'Mummy!' yelled Little Harry. For there, behind the wheel, waving and honking the horn, was Mum.

'What,' said Jem, 'is that?'

They all hurried outside.

'That,' said Dad, 'is a 1966 camper van – a twenty-three window Samba Bus – the kind enjoyed by adventurous families for over half a century now. Am I right?'

'Exactly right,' smiled Mum climbing down from the driver's seat. 'Twenty-three windows. Counted them myself. Bargain of the week at Unbeatable Motoring Bargains.'

'Half a century?' said Jem. 'Are you sure? It looks a lot older than that. It looks medieval.'

Dad peered inside. 'Look at this gorgeous old steering wheel,' he said, 'and the old-fashioned gauges. I bet the horn sounds like a choir.' He honked the horn, and the front bumper fell off and broke into pieces on the pavement.

'That kind of thing does happen with old cars,' said Dad, 'but it's nothing that can't be fixed. Look, it's got the classic split windscreen. It looks like two big eyes. When you see it from a distance it's like a big smiley face. Go on. Take a look.'

'If you look at it too hard,' said Jem, 'it will fall completely to pieces.'

Dad ignored him. 'It's got a pop-up roof compartment for extra sleeping space and a pull-out awning. Ideal for picnics on rainy days. That's the handle just over the door. All you have to do is give it a hearty tug.' He gave the handle a hearty tug. The door fell off.

'Oh,' said Mum. 'Oh dear.'

'Oh dear,' said Dad.

'I knew it,' said Mum. 'I've bought a wreck. It's just that when you talked about us all going round the world together in a car, it sounded so exciting. I thought, if we had a car . . .'

'But that's not a car,' said Jem. 'Cars have four-wheel drive, satnav and super de-icers. This has . . .'

'Charm,' said Mum.

'Exactly,' agreed Dad, looking at it sideways. 'It has charm. And character. Also the classic split windscreen.'

'What is charming,' asked Jem, 'about a bucket of rust in the shape of a van?'

'I've been so silly,' said Mum. 'I thought that you might be able to improve it – the way you've been improving the house. I thought you might be able to fix it, but I can see now that this is beyond even your talents.'

'Well,' said Dad, walking round the van and looking at it a little bit harder, 'I'm not sure about it being completely beyond my talents.'

'Oh it is,' said Mum, 'completely beyond. It would take someone much cleverer than you to fix a van like this.'

'Well, you know, I am pretty clever.'

'Not that clever.'

'Let's see.' He walked round the van again, the opposite way this time. 'You know,' he said, 'this car does need work. But a car like this is not just a heap of components. A car like this is more than the sum of its parts. Bits can fall off. You can put new bits on. The car – the heart of the car – will stay the same.'

'Cars don't actually have hearts, Dad,' said Jem.

'They do have history. A car like this, it has meant something to someone.'

'Great,' said Jem, 'so you're going to put it in a museum?'

'The word today is give it a go.'

'Which is four words,' said Lucy. 'Not meaning to be picky.'

Dad was already busy poking about in the engine. Mum looked at Lucy and Jem and winked. Then she chased all the joggers out of the kitchen, and Little Harry cheered as they ran into the road, as though it was the start of an Olympic event.

In bed that night Jem was lying awake listening to his dad still working on the engine outside when Lucy slid around the door with an armful of Little Harry's soft toys. 'He's scared that they're going to try and cuddle him to death again. You'll have to keep them in your room.'

'Can't you keep them in your room?'

'Their faces are too smiley,' she said. 'Happy faces depress me.'

'You don't think they're really going to make us go round the world in that old van, do you?' said Jem. 'I mean, even if he fixes it, it will still be an old van. No interior climate control, no airbags. It doesn't even have central locking.'

'Of course not.' Lucy was laughing. 'Who'd steal it anyway? Don't you get it? Listen, Mum is worried about Dad. He's lost his job. He's lost his car. But he hasn't lost his cleverness. He's got to find something to do with it. So he's been going round ruining my bedroom and turning Little Harry's toys against him. He's got to be stopped. You said so yourself. And that's what the camper van's for. It's a total wreck. He'll never be able to fix it really. But it'll keep him busy, keep him out of trouble, keep him happy and stop him doing his home improvements.'

'But he's working really hard on it. He's still out there now.'

'So Mum's idea is working, isn't it? You see, Jem, Dad is very clever, but Mum is cleverer.'

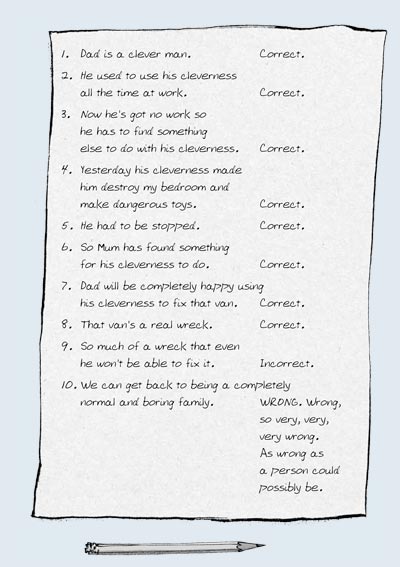

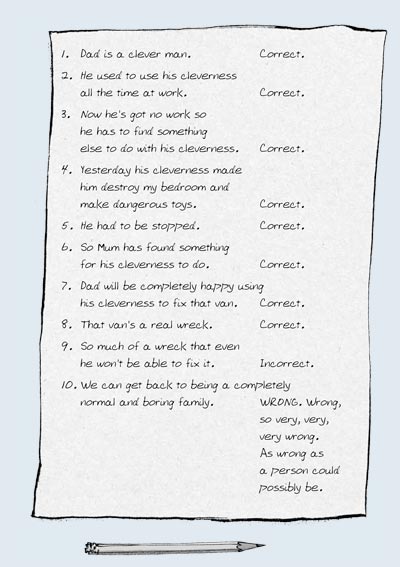

If Lucy had put all her thoughts into an essay and a teacher had marked this essay she would have got eight out of ten. And the marks would have broken down like this:

Some cars are different.

Some cars are amazing.

And the Tooting family's car was absolutely definitely not one of those.

Not amazing.

Not different.

It was so undifferent and so unamazing, in fact, that on the last day of the summer term when Lucy and Jem strolled out of the school gates and into the holidays, they walked straight past it. They didn't even notice it was there until their father popped his head out of the window and shouted, 'Lucy! Jem! Jump in! I'm giving you a lift!'

'I don't need a lift,' said Lucy, who was fifteen years old. 'I need to be alone.' Lucy always dressed completely in black, ever since last Christmas.

'Why aren't you at work?' asked Jem.

'Special occasion,' said Dad. 'I have Big News.'

'Good Big News? Or Bad Big News?' said Jem, who was a bit of a worrier.

'All Big News is tragic,' said Lucy sadly. 'Nothing good is ever news.'

'Wait and see,' said Dad. 'First we'll collect Little Harry from the childminder.'

Little Harry hated being strapped into his car seat. As he struggled to get free, Jem said, 'You have to be clipped in, in case we crash.'

'I lost my dinosaur,' said Little Harry.

'Are you going to tell us the Big Bad News now?' asked Lucy.

'It's not bad news. First we'll collect Mum from the shop.'

'You don't usually collect me from the shop,' said Mum, as she climbed into the front seat. 'Has something terrible happened?'

'Tragic news,' said Lucy.

'What tragic news?'

'Not tragic news,' said Dad. 'Big News. Excellent Big News.'

'Well, what is it?'

'I lost my dinosaur,' said Little Harry.

'Oh no,' said Mum. 'Not the lovely red remote-control one that Santa brought you?'

'Can we stop talking about the dinosaur and talk about my news, please?' said Dad.

'What news?'

'Well . . .' said Dad, '. . . I think we're going to need a takeaway to help us celebrate.'

They got the Celebration Banquet for Four with an extra portion of Chicken in Black Bean Sauce for Lucy – who liked to eat black food whenever she could. When it was all set out on the table, the lovely spicy smells curling into the air around them, Dad finally told them the excellent Big News.

'Children,' he said, 'and wife – my Excellent Big News is that –' he looked around the table, enjoying their expectant faces – 'I never have to work again! What do you think of that!?'

'Wow!' said Little Harry.

'Brilliant!' said Jem.

'That was unexpected,' said Lucy.

'How come?' said Mum.

'Because,' said Dad, 'I have been sacked! Hooray!'

'Hooray!' yelled Little Harry.

'Hooray!' re-yelled Dad.'I'm pleased that you're pleased,' said Mum, 'but are you sure it's entirely excellent news?'

'If you have no job,' said Jem, 'doesn't that mean we'll be really poor and starve to death?'

'No,' said Dad. 'It means we'll be able to do whatever we want and go wherever we like. The word today,' he said, 'is opportunity.'

'I want my dinosaur back!' yelled Little Harry.

Dad explained the details. 'Since the day I left school,' he said, 'I have worked in a factory making tiny, tiny parts for really big machines. But now the company has a new contract making even tinier parts for even bigger machines. My fingers are just too big for the job. So they said they had to let me go.'

'Go where?' said Jem.

'Go anywhere we like,' said Dad.

'When you say anywhere,' said Jem, 'does that include abroad?' No one in the Tooting family had ever been abroad before.

'Anywhere,' said Dad, 'means anywhere in the world.' He smiled at Mum. 'And, dearest, you get first pick.'

Mum blushed a little and said, 'Well you always promised to take me to Paris.'

'Paris,' he said, 'is yours. The moment we are packed. Lucy?'

'Me?' said Lucy. 'I don't want to go anywhere. I want to spend my days in my room, now that I've finally got it the way I like it.' Lucy had got rid of all the ornaments and dancing certificates from her room, painted the walls and her bookcase black. Dyed her duvet. And her pillowslip.

'You must want to go somewhere?'

'I suppose I wouldn't mind seeing the pyramids. I could sit in the desert looking at the Sphinx and think about dead pharaohs, with their gold and jewels, lying there in the desert night. Dead, dead, dead.'

'I can see we're going to need to plan our route,' said Dad. 'Go and get that map of the world from your bedroom wall.'

'The map of the world isn't on my bedroom wall any more,' said Lucy. 'The colours were too bright – yellow and blue and pink. Pastel colours depress me.'

'But I've had that map since I was a little boy. I won it for being punctual. It says so on the back. What have you done with it?'

'I stuck it up on Jem's wall.'

'Jem—'

'It was completely out of date. There were countries on there that were shut down years ago and new countries that weren't even mentioned. Instead of France it had something called Gaul.'

'It was supposed to be a historical map.'

'That's what I said, out of date. I put it in recycling.'

'What? Do you know how often I had to be punctual to win that prize?'

'Why would you want an out-of-date map when there's really good satnav in the car? A map like that could be dangerous.'

'Dangerous? How?'

'If you tried to use it you would get lost. People get lost all the time. Cities get lost, even.'

'What cities get lost?' said Lucy.

'El Dorado. Camelot. Troy. Xanadu. Atlantis. They were all big cities once and now no one knows where they are. They got lost. I bet it was because of out-of-date maps.'

'Maps go out of date,' said Dad, 'because countries change. And people can go out of date because their fingers are too big for the machines. That doesn't mean they should be put in a bin. Just because something's out of date doesn't mean it's no use.'

'Dad, I was talking about maps, not fingers,' said Jem.

'I didn't mean—'

'And it's all fine anyway,' said Mum, 'because I took the map out of recycling again. Here it is . . .' She spread it out on the table and touched the back of Dad's hand.

'I've always been very proud of your father's punctuality,' she said. 'It's one of his most attractive qualities, along with his boyish smile.' Dad smiled his boyish smile.

'Now, Jem, you said you wanted to go to El Dorado. Show your dad where it is on the map.'

'I don't know where it is on the map. That's the point. It's lost. I was making a point about how easy it is to get lost. If a big city can get lost, a small person can get lost.'

'It's somewhere around here,' said Dad, pointing to South America.

'Well then,' said Mum, 'we'll stop and ask when we get to the general area. The locals are bound to know. Little Harry, what about you?'

'Dinosaurs!' yelled Little Harry.

'We'll try our best,' said Dad. 'So . . . what have we got? Paris for Mum, Cairo for Lucy, El Dorado for Jem—'

'I really don't want to go to El Dorado,' said Jem.

'. . . and last of all, the North Pole for me.'

'That's the South Pole,' said Jem. 'You've got the map upside down. See what I mean about how easy it is to get lost?'

'Can you really drive to the North Pole in a car?' said Lucy. 'Wouldn't you be overwhelmed by blizzards and buried in avalanches and left untouched and frozen in the snow for hundreds of years, like fish fingers? Dead, dead, dead.'

'No,' said Jem. 'Because our car's got four-wheel drive and a super de-icer. And satnav. It can go anywhere in the whole world and never get stuck and never get lost.'

That's when the doorbell rang.

At the door was a nice young man in a blazer with a plastic identity card clipped to his lapel. 'Hello,' said Dad, reading the badge, 'Bernard.'

'Good evening, Mr Tooting.' Bernard smiled. 'I work for Very Small Parts For Very Big Machines.'

'Oh!' said Dad. 'So do I!'

'Not any more you don't.' Bernard smiled again.

'Oh yes, I forgot.'

'Perhaps you also forgot that this car – with its satnav, four-wheel drive and super de-icer – belongs to the company?'

'Oh,' said Dad. 'I did forget that. Yes.'

'Keys, please.' Still smiling, Bernard put his hand out and Dad gave him the car keys. Bernard drove away in the car. Mum put her hand gently on Dad's shoulder.

'Never mind,' she said.

'I've got no job.'

'We'll manage,' said Mum.

'I've got big fingers.'

'I like your fingers.'

'I've got no car,' said Dad.

'We'll walk,' said Mum.

'Not to Paris.'

'No.'

'Not to Cairo.'

'No.'

'Not to El Dorado, or the North Pole. We'll never go to any of those places. We'll never go anywhere.'

He stood and watched until the car had disappeared around the corner.

'The word today,' he said, 'is stuck.'

Mum went back to the supper table.

'When your father comes back,' she said, 'he may well be very unhappy.'

'Why?' said Jem.

'Because he's got no job, no car and no prospects,' said Lucy.

'I wouldn't say no prospects,' said Mum.

'He's much too old to get another job.'

'I lost my dinosaur,' said Little Harry.

But when Dad came back to the table, he said, 'Pass me a prawn cracker, Jem,' and leaned back in his chair with a big smile on his face. 'I am so glad,' he said, 'that that car has finally gone. I never wanted to travel the world. Now I'll be able to concentrate on my plans for this house.'

'You've got plans for the house?' asked Mum. 'What sort of plans?'

'The word today,' said Dad, 'is home improvement.'

There was a terrible, blood-curdling scream, a scream that rattled windows seven streets away.

When Lucy woke up on that first day of the summer holidays, she was confronted with her worst nightmare. While she was sleeping, someone had somehow covered her black walls with jolly blue wallpaper with daisies on it.

'My eyes!' shrieked Lucy. 'The wallpaper is blinding me!' She covered her face with her hands and, peeping out through her fingers, saw Dad up a ladder hanging a strip of the blue daisy wallpaper.

'What do you think?' he asked. 'Thought I'd brighten the place up a bit. Your room was so gloomy.'

'I like gloomy,' said Lucy. 'Gloomy is the point. I worked hard on gloomy. I painted it with three coats of gloomy paint. And what is that terrible smell?'

A little cloud of thick black smoke was curling from a hot, bubbling hole in the top of her skull-shaped reading lamp. 'My skull,' she shrieked. 'My skull is melting!' The lamp was charred and twisted and slumped to one side.

'The light seemed a bit dim so I put a more powerful bulb in it. Maybe a bit too powerful.'

'I'm being poisoned by my own bedside lamp!'

From the next room came a cry of, 'Help! Help! Help me!'

'Oh,' said Dad. 'Sounds like Jem's awake.'

'It sounds like Jem's in mortal danger.'

'I think he's just really surprised at what I've done to his room.'

Jem had been woken up by a strange, electric whining. When he opened his eyes, a small blue object whizzed right past his face. He barely had a chance to blink when a small red object rattled past even closer. He just had time to see that the objects were car-shaped. Tiny cars were flying round his room, skimming by his face, like angry insects.

'Help!' he yelled, sliding under the duvet. 'Help!' He didn't shout anything more specific because he couldn't figure out what kind of help a person should ask for if attacked by tiny cars – presumably driven by tiny men.

The explanation was simple enough. When Dad was ten years old, he had woken up on his birthday to find that his dad had assembled an amazing Scalextric track in the bedroom he shared with his brother. It was one of the happiest memories of his life – a plastic racetrack, two racing cars – one blue and one red – and a little man with a chequered flag, all set up and ready to go. They spent the whole day racing each other round and round that track. For years afterwards they used pocket money to get extra track and the round circuit grew into a spaghetti of twists, turns, chicanes and flyovers. They grew out of it but Dad could never bear to give it away or throw it out so it had ended up in the loft. He always meant to get it down and fix it up so that Jem could play with it. Now that he'd been sacked he finally had the time to get the pieces down, make sure the wheels were oiled and the wires were snug, sneak into Jem's room and snap together a race course that whirled around the table legs, soared over his bed, swung in and out of the windowsill and filled the room with speed and the smell of hot metal.

'What do you think?' said Dad, sticking his head round the door.

'What's it for?'

'We can race against each other.'

'Haven't you heard of computers? We can race against each other on a range of platforms in any format we like. We can race as elephants, rockets, chariots – not red and blue plastic cars. And you don't have to tidy up afterwards and it's not dangerous. That's why people like to play on their computers and why they put this stuff in the dump.'

'How is this dangerous?'

'Electric wires, bits of plastic flying around the room at speed. Of course it's dangerous . . .' Just as he said that, the blue car missed the turn, shot off the end of the track, tumbled through the air and whacked Dad in the middle of his forehead. For a second it looked like he was going to fall over. Then, 'That's all part of the fun of it!' He smiled and wiped the blood away. 'The word today is fun.'

Little Harry had a dream about dinosaurs. It wasn't a nightmare. He loved dinosaurs and in the dream they were picking him up and throwing him to each other, slapping him into the air with their tails and bouncing him off their horns, and all the time he was laughing and gurgling. When he woke up, Dad was sitting on the end of his bed.

'I know what you're going to say, Little Harry,' he said. 'You say the same thing every morning. Every morning you say, "Play with me". Every morning I say I can't because I'm going to work. But this morning is different. Go on, say, "Play with me".'

'Dinosaur!' said Little Harry.

'No, like this . . . Play with me.'

'Please dinosaur.'

'Play. With. Me . . .' The moment Dad said this, there was a strange whirring from the toy box at the end of Little Harry's bed. The whirring was followed by a clicking.

'You're always asking people to play with you,' Dad explained, 'when they're too busy. So I've used some of the skills and expertise I learned in the twenty years I worked without complaint and never once being late at Very Small Parts For Very Big Machines. I have used those skills so that instead of playing with toys like other children, you will have toys that play with you!'

Little Harry was staring at the toy box. His eyes were growing wider and wider.

'Voice-activated,' said Dad. 'From now on, whenever you say "Play with me", your toys will just get up and play with you . . .'

Harry's eyes were now so round they looked as though they were going to fall out of his face. A dozen Playmobil men clambered out of the box and marched towards his bed, their plastic arms held out in front of them like tiny primary-colour zombies. They were followed by some wooden knights brandishing sharp little wooden lances, and a family of grinning yellow ducks that rocked themselves bit by bit across the carpet. Toy cars whizzed towards him from every dusty corner of the room.

Little Harry saw this brightly coloured army of toys coming towards him and he cried like a baby. He was a baby.

A large snake made of red and blue felt reared up from behind the washing basket and flung itself on to the bed. A massive fuzzy blue giraffe stood up, steadied itself and began to goose-step jerkily towards him.

'They all want to play,' said Dad. 'You want to play and they want to play. It's the ideal arrangement.'

The pterodactyl mobile that hung from Little Harry's lampshade spun faster and faster until the tiny pterodactyls broke free and came buzzing round his head like Jurassic fighter planes. Desperately Little Harry tried to bat them away.

'Don't worry, they won't hurt you.' Dad smiled. 'I fitted little sensors to the front so that they don't bump into you. I'm particularly proud of those. Well, you have fun. I'm going to go and make some tea.'

Dad strolled out of the room, but when Little Harry tried to follow him the big blue-and-red snake wrapped its fluffy coils around his middle and began to squeeze. Little Harry screamed louder than ever, though his screams were muffled slightly by the massive giraffe which was now headbutting him, softly and repeatedly. He was still there being cuddled by the snake and headbutted by the giraffe when Lucy came into his room to look for a paintbrush.

'Jem! Quick!' she yelled. 'Little Harry's toys have gone nutzoid!'

They peeled the snake off Little Harry and forced the giraffe back into the corner. They locked the little wooden knights away and tied the pterodactyls down.

'What happened?' said Jem once Little Harry had been rescued from his toys.

'Isn't it obvious?' said Lucy.

'Home Improvements,' said Jem.

'Dad has got to be stopped,' said both of them.

Truly Jem and Lucy thought that as soon as Mum found out about the headbutting giraffes and melting skulls she would put an end to home improvements. But that afternoon, as she trudged up the garden path after a hard day's work at Unbeatable Motoring Bargains, a very refreshing thing happened. The front door opened all by itself and a bright little voice said, 'Do come in. The kettle is on.'

'What a lovely homecoming,' said Mum, strolling into the kitchen just as the kettle came to the boil.

'I installed an automatic self-opening on the front door,' explained Dad, 'and hooked it up to the kettle.'

'My genius.' Mum smiled.

'The word today,' said Dad, 'is welcome home.'

'That's two words,' said Lucy.

'Dad made a robot snake that tried to strangle Little Harry,' said Jem.

'It was a cuddly snake. It was just cuddling him,' explained Dad. 'From now on, whenever you come home, the kettle will always be boiling.'

'Also, Jem's bedroom is now a death trap,' said Lucy.

'A work in progress,' said Mum, sipping her tea. 'Be patient. Your father can't improve every aspect of our lives in one day.'

'He made my skull melt,' said Lucy.

'Teething problems,' said Mum. 'Any man who can get a door to make a lovely cup of tea like this can do anything. Give him time.'

As far as Mum was concerned, a self-opening front door that made tea was a magnificent home improvement. The only problem was, it was magnificent for anyone who happened to be passing. When Mum came down next morning, the milkman and the paper boy were already in the kitchen guzzling tea and Krispies. The paper boy looked hard at Mum and said, 'I know you from somewhere.'

'I live here,' said Mum. 'Those are my Krispies.'

'Thanks for sharing,' said the paper boy.

There was a sudden draught of cold air as the front door opened itself and invited a passing jogger in.

'I,' said Mum, 'have to go to work.'

Off she went.

The postman, the milkman and the paper boy all left to resume their work quite soon after Mum, but the jogger was not in any hurry. He was still there when Lucy and Jem came down to breakfast. Still there when Dad came in to cook lunch. Every now and then he did stand up as if about to leave, but each time he did the front door would ask another jogger in and the joggers always seemed to know each other and have plenty to talk about. Slowly the kitchen filled up so that by four o'clock it was an impenetrable mass of joggers. If Jem or Lucy looked in, someone would push a mug at them and say, 'More tea, please,' or, 'We've run out of milk.' The children parked themselves miserably on the bottom stair, waiting for the day to end.

'I'm hungry,' said Little Harry.

'We have been excluded from our own kitchen,' said Lucy.

'I'm hungry,' said Little Harry.

'So am I, but there's nothing we can do about it just now.'

'I'm hungry,' said Little Harry.

'Yes. You've mentioned this. Why can't we just be an ordinary family like we used to be?'

'You were ordinary,' said Lucy. 'I never was.'

Outside the house someone was happily honking a car horn.

'Who's that?'

'It doesn't matter who it is,' said Lucy. 'It doesn't matter if it's Lord Voldemort and his wicked stepmother, the front door will still open and ask them in for tea.'

The front door did open and did ask them in for tea, and when it did they saw, standing in the road, a dirty blue-and-cream camper van with rusty bumpers and one window missing.

'Mummy!' yelled Little Harry. For there, behind the wheel, waving and honking the horn, was Mum.

'What,' said Jem, 'is that?'

They all hurried outside.

'That,' said Dad, 'is a 1966 camper van – a twenty-three window Samba Bus – the kind enjoyed by adventurous families for over half a century now. Am I right?'

'Exactly right,' smiled Mum climbing down from the driver's seat. 'Twenty-three windows. Counted them myself. Bargain of the week at Unbeatable Motoring Bargains.'

'Half a century?' said Jem. 'Are you sure? It looks a lot older than that. It looks medieval.'

Dad peered inside. 'Look at this gorgeous old steering wheel,' he said, 'and the old-fashioned gauges. I bet the horn sounds like a choir.' He honked the horn, and the front bumper fell off and broke into pieces on the pavement.

'That kind of thing does happen with old cars,' said Dad, 'but it's nothing that can't be fixed. Look, it's got the classic split windscreen. It looks like two big eyes. When you see it from a distance it's like a big smiley face. Go on. Take a look.'

'If you look at it too hard,' said Jem, 'it will fall completely to pieces.'

Dad ignored him. 'It's got a pop-up roof compartment for extra sleeping space and a pull-out awning. Ideal for picnics on rainy days. That's the handle just over the door. All you have to do is give it a hearty tug.' He gave the handle a hearty tug. The door fell off.

'Oh,' said Mum. 'Oh dear.'

'Oh dear,' said Dad.

'I knew it,' said Mum. 'I've bought a wreck. It's just that when you talked about us all going round the world together in a car, it sounded so exciting. I thought, if we had a car . . .'

'But that's not a car,' said Jem. 'Cars have four-wheel drive, satnav and super de-icers. This has . . .'

'Charm,' said Mum.

'Exactly,' agreed Dad, looking at it sideways. 'It has charm. And character. Also the classic split windscreen.'

'What is charming,' asked Jem, 'about a bucket of rust in the shape of a van?'

'I've been so silly,' said Mum. 'I thought that you might be able to improve it – the way you've been improving the house. I thought you might be able to fix it, but I can see now that this is beyond even your talents.'

'Well,' said Dad, walking round the van and looking at it a little bit harder, 'I'm not sure about it being completely beyond my talents.'

'Oh it is,' said Mum, 'completely beyond. It would take someone much cleverer than you to fix a van like this.'

'Well, you know, I am pretty clever.'

'Not that clever.'

'Let's see.' He walked round the van again, the opposite way this time. 'You know,' he said, 'this car does need work. But a car like this is not just a heap of components. A car like this is more than the sum of its parts. Bits can fall off. You can put new bits on. The car – the heart of the car – will stay the same.'

'Cars don't actually have hearts, Dad,' said Jem.

'They do have history. A car like this, it has meant something to someone.'

'Great,' said Jem, 'so you're going to put it in a museum?'

'The word today is give it a go.'

'Which is four words,' said Lucy. 'Not meaning to be picky.'

Dad was already busy poking about in the engine. Mum looked at Lucy and Jem and winked. Then she chased all the joggers out of the kitchen, and Little Harry cheered as they ran into the road, as though it was the start of an Olympic event.

In bed that night Jem was lying awake listening to his dad still working on the engine outside when Lucy slid around the door with an armful of Little Harry's soft toys. 'He's scared that they're going to try and cuddle him to death again. You'll have to keep them in your room.'

'Can't you keep them in your room?'

'Their faces are too smiley,' she said. 'Happy faces depress me.'

'You don't think they're really going to make us go round the world in that old van, do you?' said Jem. 'I mean, even if he fixes it, it will still be an old van. No interior climate control, no airbags. It doesn't even have central locking.'

'Of course not.' Lucy was laughing. 'Who'd steal it anyway? Don't you get it? Listen, Mum is worried about Dad. He's lost his job. He's lost his car. But he hasn't lost his cleverness. He's got to find something to do with it. So he's been going round ruining my bedroom and turning Little Harry's toys against him. He's got to be stopped. You said so yourself. And that's what the camper van's for. It's a total wreck. He'll never be able to fix it really. But it'll keep him busy, keep him out of trouble, keep him happy and stop him doing his home improvements.'

'But he's working really hard on it. He's still out there now.'

'So Mum's idea is working, isn't it? You see, Jem, Dad is very clever, but Mum is cleverer.'

If Lucy had put all her thoughts into an essay and a teacher had marked this essay she would have got eight out of ten. And the marks would have broken down like this:

The Book / Frank Cottrell Boyce / Drawing Competition / Have You Seen Chitty? / Fun Stuff! / Home

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang is a trademark of Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation and is used under licence by the Ian Fleming Will Trust. All Rights Reserved.

This site is run by Pan Macmillan